Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Korean Acad Nurs > Volume 55(2); 2025 > Article

-

Research Paper

- Impact of smoking on diabetes complications: a secondary analysis of the Korean National Health Insurance Service-health screening cohort (2002–2019)

-

Seonmi Yeom1

, Youngran Yang1,2

, Youngran Yang1,2

-

Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing 2025;55(2):222-235.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.24109

Published online: April 21, 2025

1Research Institute of Nursing Science, College of Nursing, Jeonbuk National University, Jeonju, Korea

2Biomedical Research Institute, Jeonbuk National University Hospital, Jeonju, Korea

- Corresponding author: Youngran Yang Research Institute of Nursing Science, College of Nursing, Jeonbuk National University, 567 Baekje-daero, Deokjin-gu, Jeonju 54896, Korea E-mail: youngran13@jbnu.ac.kr

- †This work was presented at 2024 CUK-AAPINA Conference, May, 2024, Seoul, South Korea.

© 2025 Korean Society of Nursing Science

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivs License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0) If the original work is properly cited and retained without any modification or reproduction, it can be used and re-distributed in any format and medium.

- 2,102 Views

- 120 Download

Abstract

-

Purpose

- This study aimed to examine the effects of smoking on the incidence of macrovascular and microvascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes.

-

Methods

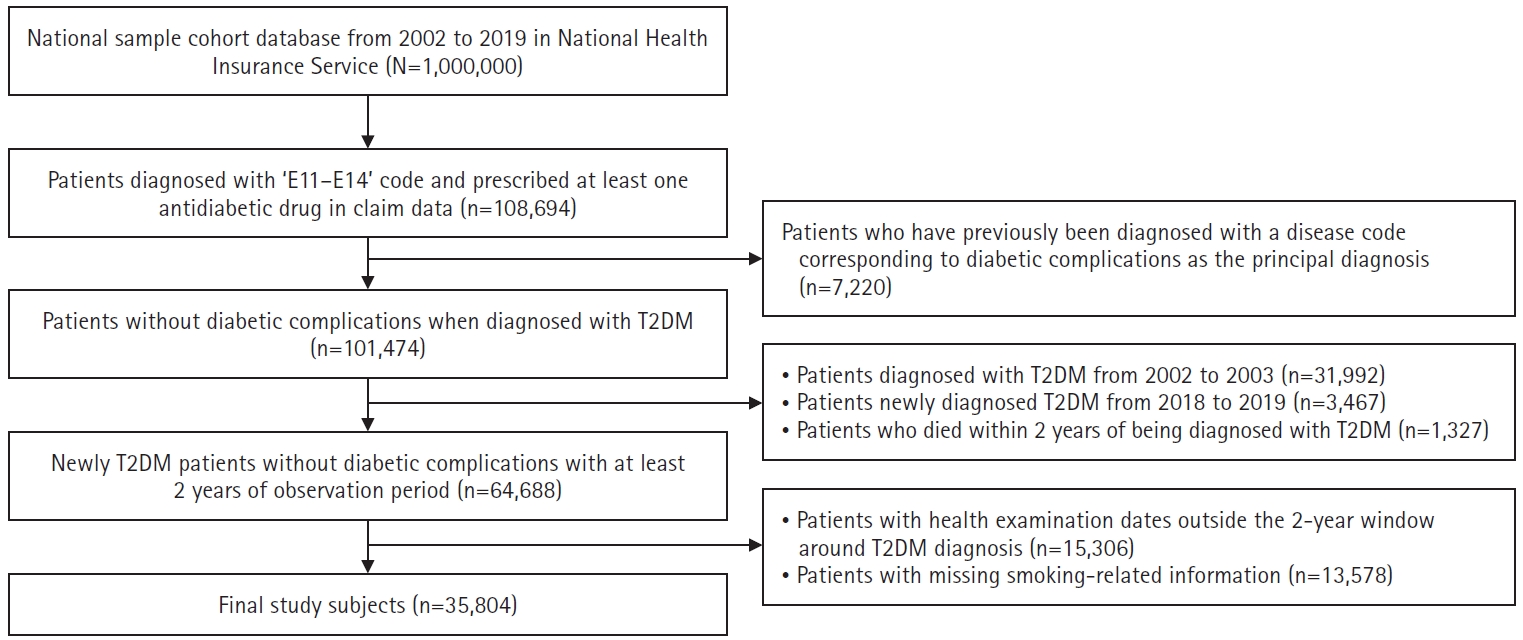

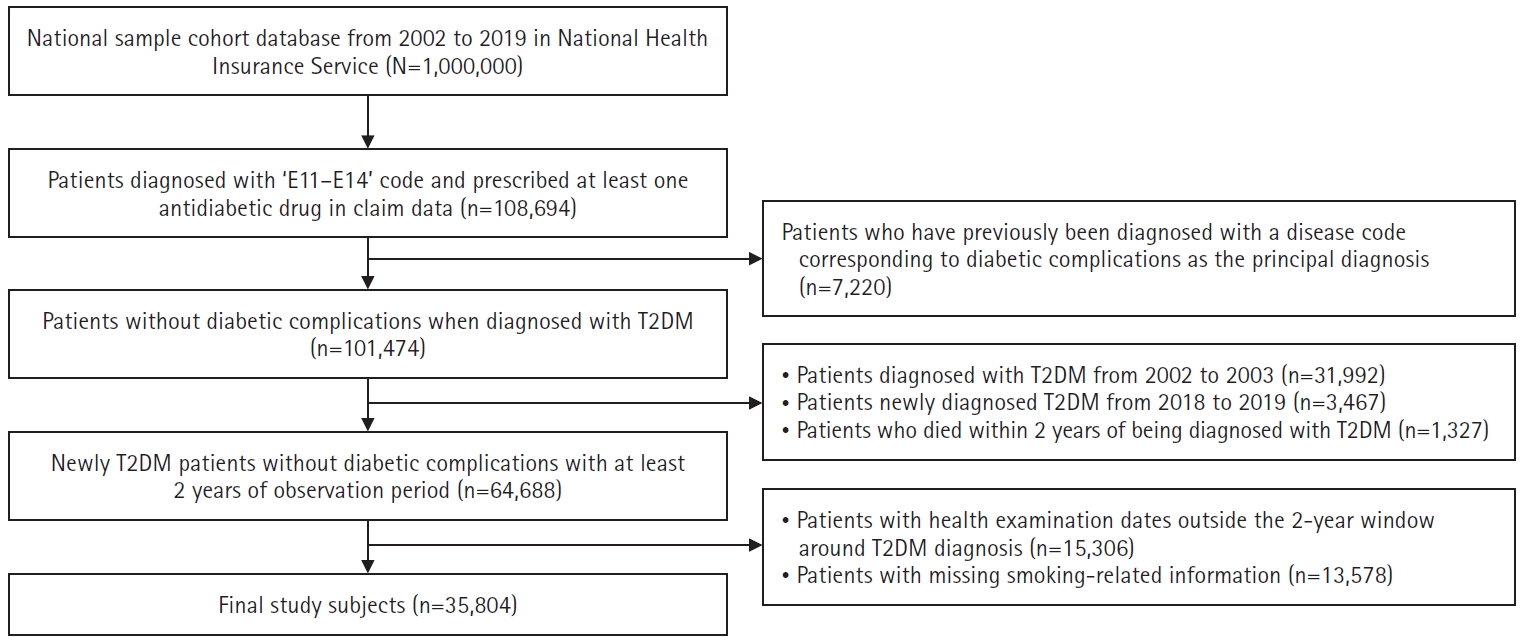

- We analyzed 35,804 patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes between 2004 and 2017 using the Korean National Health Insurance Service–National Health Screening Cohort (2002–2019). Smoking status was categorized into never, former, and current smokers, with further classification based on duration of smoking and daily smoking amount. We conducted survival analysis using a Cox proportional hazards model.

-

Results

- Both former and current smokers had significantly elevated risks of macrovascular complications compared to non-smokers, with hazard ratios (HRs) of 1.60 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.49–1.66) and 1.10 (95% CI, 1.08–1.17), respectively. Long-term smokers (over 30 years) had significantly higher risks of both macrovascular (HR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.29–1.42) and microvascular complications (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.30–1.42). Heavy smokers (over 2 packs/day) had a higher risk of developing macrovascular (HR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.30–1.64) and microvascular (HR, 1.78; 95% CI, 1.60–1.98) complications than never smokers. Notably, former smokers had increased risks of developing neuropathy (HR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.31–1.49), nephropathy (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.16–1.39), and retinopathy (HR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.39–1.60).

-

Conclusion

- Patients with type 2 diabetes and a history of smoking are at higher risk of developing macrovascular and microvascular complications. Smoking cessation, along with reducing smoking duration and amount, is crucial for lowering these risks.

Introduction

Methods

Results

Discussion

Conclusion

-

Conflicts of Interest

Youngran Yang has been the editorial board member of JKAN since 2024 but has no role in the review process. Except for that, no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

Acknowledgements

None.

-

Funding

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (2021R1A2C2092656).

-

Data Sharing Statement

Please contact the corresponding author for data availability.

-

Author Contributions

Conceptualization or/and Methodology: SY, YY. Data curation or/and Analysis: SY, YY. Funding acquisition: YY. Investigation: SY, YY. Project administration or/and Supervision: YY. Resources or/and Software: SY, YY. Validation: SY, YY. Visualization: SY, YY. Writing: original draft or/and Review & Editing: SY, YY. Final approval of the manuscript: SY, YY.

Article Information

Values are presented as number of frequency (row %), calculated as (patients with the complication/total patients in the category)×100, rounded to one decimal place. Individual complication counts include overlaps, while all complications exclude them.

CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; CeVD, cerebrovascular disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; MPRm, medication possession ratio modified; NEPH, nephropathy; NEURO, neuropathy; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; RETINO, retinopathy.

a)Total number for this group=39.4% of the total (35,804). b)Non-drinkers were excluded.

Adjusted for gender, age, household income, CCI score, MPRm, heavy drinking, and physical activity.

Adj.HR, adjusted hazard ratio; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; CeVD, cerebrovascular disease; CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; MPRm, medication possession ratio modified; NEPH, nephropathy; NEURO, neuropathy; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; Ref, reference; RETINO, retinopathy.

- 1. International Diabetes Federation (IDF). IDF diabetes atlas 2021, 10th edition [Internet]. IDF; c2021 [cited 2024 Feb 6]. Available from: https://diabetesatlas.org/atlas/tenth-edition/

- 2. Korean Diabetes Association (KDA). Diabetes fact sheet in Korea 2022 [Internet]. KDA; c2022 [cited 2024 Feb 6]. Available from: https://www.diabetes.or.kr/bbs/?code=eng_fact_sheet&mode=view&number=761&page=1&code=eng_fact_sheet

- 3. Forbes JM, Cooper ME. Mechanisms of diabetic complications. Physiol Rev. 2013;93(1):137-188. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00045.2011ArticlePubMed

- 4. Zheng Y, Ley SH, Hu FB. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(2):88-98. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2017.151ArticlePubMed

- 5. Pearce I, Simó R, Lövestam-Adrian M, Wong DT, Evans M. Association between diabetic eye disease and other complications of diabetes: implications for care: a systematic review. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21(3):467-478. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.13550ArticlePubMedPMC

- 6. Zhang Y, Wu J, Chen Y, Shi L. EQ-5D-3L decrements by diabetes complications and comorbidities in China. Diabetes Ther. 2020;11(4):939-950. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-020-00788-zArticlePubMedPMC

- 7. Śliwińska-Mossoń M, Milnerowicz H. The impact of smoking on the development of diabetes and its complications. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2017;14(4):265-276. https://doi.org/10.1177/1479164117701876ArticlePubMed

- 8. Kar D, Gillies C, Zaccardi F, Webb D, Seidu S, Tesfaye S, et al. Relationship of cardiometabolic parameters in non-smokers, current smokers, and quitters in diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15(1):158. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-016-0475-5ArticlePubMedPMC

- 9. Pan A, Wang Y, Talaei M, Hu FB. Relation of smoking with total mortality and cardiovascular events among patients with diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Circulation. 2015;132(19):1795-1804. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017926ArticlePubMedPMC

- 10. Liao D, Ma L, Liu J, Fu P. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for diabetic nephropathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0210213. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210213ArticlePubMedPMC

- 11. American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 5. Facilitating behavior change and well-being to improve health outcomes: standards of medical care in diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(Suppl 1):S60-S82. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc22-S005ArticlePubMed

- 12. Campagna D, Alamo A, Di Pino A, Russo C, Calogero AE, Purrello F, et al. Smoking and diabetes: dangerous liaisons and confusing relationships. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2019;11:85. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-019-0482-2ArticlePubMedPMC

- 13. Lee H, Lee M, Park G, Khang AR. Prevalence of chronic diabetic complications in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a retrospective study based on the National Health Insurance Service-National Health Screening Cohort in Korea, 2002-2015. Korean J Adult Nurs. 2022;34(1):39-50. https://doi.org/10.7475/kjan.2022.34.1.39Article

- 14. Yoo H, Choo E, Lee S. Study of hospitalization and mortality in Korean diabetic patients using the diabetes complications severity index. BMC Endocr Disord. 2020;20(1):122. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-020-00605-5ArticlePubMedPMC

- 15. Young BA, Lin E, Von Korff M, Simon G, Ciechanowski P, Ludman EJ, et al. Diabetes complications severity index and risk of mortality, hospitalization, and healthcare utilization. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(1):15-23. PubMedPMC

- 16. Glasheen WP, Renda A, Dong Y. Diabetes Complications Severity Index (DCSI): update and ICD-10 translation. J Diabetes Complications. 2017;31(6):1007-1013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2017.02.018ArticlePubMed

- 17. Lee SH. Difference in incidence of diabetic complication according to smoking status change in type 2 diabetic patients-National Health Insurance Services Medical a check-up cohort database from 2002 through 2013 [master’s thesis]. Seoul: Yonsei University; 2018.

- 18. Hess LM, Raebel MA, Conner DA, Malone DC. Measurement of adherence in pharmacy administrative databases: a proposal for standard definitions and preferred measures. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40(7-8):1280-1288. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1H018ArticlePubMed

- 19. Balkhi B, Alwhaibi M, Alqahtani N, Alhawassi T, Alshammari TM, Mahmoud M, et al. Oral antidiabetic medication adherence and glycaemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional retrospective study in a tertiary hospital in Saudi Arabia. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7):e029280. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029280ArticlePubMedPMC

- 20. Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, Fushimi K, Graham P, Hider P, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676-682. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwq433ArticlePubMed

- 21. Jung JG, Kim JS, Yoon SJ, Lee S, Ahn SK. Korean alcohol guidelines for primary care physician. Korean J Fam Pract. 2021;11(1):14-21. https://doi.org/10.21215/kjfp.2021.11.1.14Article

- 22. Roderick P, Turner V, Readshaw A, Dogar O, Siddiqi K. The global prevalence of tobacco use in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;154:52-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2019.05.035ArticlePubMed

- 23. Qin R, Chen T, Lou Q, Yu D. Excess risk of mortality and cardiovascular events associated with smoking among patients with diabetes: meta-analysis of observational prospective studies. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167(2):342-350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.12.100ArticlePubMed

- 24. Szwarcbard N, Villani M, Earnest A, Flack J, Andrikopoulos S, Wischer N, et al. The association of smoking status with glycemic control, metabolic profile and diabetic complications: results of the Australian National Diabetes Audit (ANDA). J Diabetes Complications. 2020;34(9):107626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2020.107626ArticlePubMed

- 25. Feodoroff M, Harjutsalo V, Forsblom C, Thorn L, Wadén J, Tolonen N, et al. Smoking and progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 1 diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2016;53(4):525-533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-015-0822-0ArticlePubMed

- 26. Park SE, Seo MH, Cho JH, Kwon H, Kim YH, Han KD, et al. Dose-dependent effect of smoking on risk of diabetes remains after smoking cessation: a nationwide population-based cohort study in Korea. Diabetes Metab J. 2021;45(4):539-546. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2020.0061ArticlePubMedPMC

- 27. Yeom H, Lee JH, Kim HC, Suh I. The association between smoking tobacco after a diagnosis of diabetes and the prevalence of diabetic nephropathy in the Korean male population. J Prev Med Public Health. 2016;49(2):108-117. https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.15.062ArticlePubMedPMC

- 28. Tang R, Yang S, Liu W, Yang B, Wang S, Yang Z, et al. Smoking is a risk factor of coronary heart disease through HDL-C in Chinese T2DM patients: a mediation analysis. J Healthc Eng. 2020;2020:8876812. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8876812ArticlePubMedPMC

- 29. Rawshani A, Rawshani A, Franzén S, Sattar N, Eliasson B, Svensson AM, et al. Risk factors, mortality, and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(7):633-644. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1800256ArticlePubMed

- 30. Lee HJ, Kim YS, Park I. Calculation of sample size in clinical trials. Clin Should Elbow. 2013;16(1):53-57. https://doi.org/10.5397/CiSE.2013.16.1.53Article

- 31. Xia N, Morteza A, Yang F, Cao H, Wang A. Review of the role of cigarette smoking in diabetic foot. J Diabetes Investig. 2019;10(2):202-215. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.12952ArticlePubMedPMC

- 32. Cai X, Chen Y, Yang W, Gao X, Han X, Ji L. The association of smoking and risk of diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Endocrine. 2018;62(2):299-306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-018-1697-yArticlePubMed

- 33. Park SK, Kim MH, Jung JY, Oh CM, Ha E, Nam DJ, et al. Changes in smoking status, amount of smoking and their relation to the risk of microvascular complications in men with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2023;39(8):e3697. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.3697ArticlePubMed

- 34. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Diabetes and smoking [Internet]. CDC; c2024 [cited 2024 Dec 12]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/risk-factors/diabetes-and-smoking.html#cdc_risk_factors_protect_factor-quit-for-good

- 35. Lindson N, Klemperer E, Hong B, Ordóñez-Mena JM, Aveyard P. Smoking reduction interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;9(9):CD013183. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013183.pub2ArticlePubMedPMC

- 36. Livingstone-Banks J, Norris E, Hartmann-Boyce J, West R, Jarvis M, Chubb E, et al. Relapse prevention interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2019(10):CD003999. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003999.pub6ArticlePubMedPMC

References

Appendix

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

Fig. 1.

| Characteristic | Total (N=35,804) | Onset of diabetic complications | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All complications | Macrovascular complications | Microvascular complications | |||||||||||||||||

| All | CeVD | CVD | PVD | All | NEPH | NEURO | RETINO | ||||||||||||

| n (%) | n (%) | p | n (%) | p | n (%) | p | n (%) | p | n (%) | p | n (%) | p | n (%) | p | n (%) | p | n (%) | p | |

| All | 29,205 (81.6) | 21,481 (60.0) | 6,476 (18.1) | 13,935 (38.9) | 14,502 (40.5) | 24,564 (68.6) | 7,929 (22.2) | 16,951 (47.3) | 14,205 (40.0) | ||||||||||

| Gender | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | .070 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||||||||

| Men | 20,120 (56.2) | 15,750 (78.3) | 11,363 (56.5) | 3,214 (16.0) | 7,325 (36.4) | 7,508 (37.3) | 12,997 (64.6) | 4,385 (21.8) | 8,669 (43.1) | 7,190 (35.7) | |||||||||

| Women | 15,684 (43.8) | 13,455 (85.8) | 10,118 (64.5) | 3,262 (20.8) | 6, 610 (42.1) | 6,994 (44.6) | 11,567 (73.8) | 3,544 (22.6) | 8,282 (52.8) | 7,015 (44.7) | |||||||||

| Age (yr) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||||||||

| 18–29 | 309 (0.8) | 210 (68.0) | 101 (32.7) | 8 (2.6) | 47 (15.2) | 79 (25.6) | 182 (58.9) | 64 (20.7) | 104 (33.7) | 122 (39.5) | |||||||||

| 30–39 | 2,083 (5.8) | 1,415 (67.9) | 783 (37.6) | 90 (4.3) | 415 (19.9) | 552 (26.5) | 1,219 (58.5) | 443 (21.3) | 711 (34.1) | 690 (33.1) | |||||||||

| 40–49 | 7,362 (20.6) | 5,531 (75.1) | 3,642 (49.5) | 696 (9.5) | 2,074 (28.2) | 2,622 (35.6) | 4,639 (63.0) | 1,494 (20.3) | 2,942 (40.0) | 2,695 (36.6) | |||||||||

| 50–59 | 11,842 (33.1) | 9,642 (81.4) | 6,917 (58.4) | 1,770 (15.0) | 4,338 (36.6) | 4,741 (40.0) | 8,146 (68.8) | 2,548 (21.5) | 5,573 (47.1) | 4,826 (40.8) | |||||||||

| 60–69 | 9,055 (25.3) | 7,858 (86.8) | 6,243 (69.0) | 2,261 (25.0) | 4,304 (47.5) | 4,166 (46.0) | 6,678 (73.8) | 2,138 (23.6) | 4,841 (53.5) | 4,085 (45.1) | |||||||||

| ≥70 | 5,153 (14.4) | 4,549 (88.3) | 3,795 (73.7) | 1,651 (32.0) | 2,757 (53.5) | 2,342 (45.5) | 3,700 (71.8) | 1,242 (24.1) | 2,780 (54.0) | 1,787 (34.7) | |||||||||

| Household income | .885 | .565 | .003 | .001 | .148 | .985 | .115 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||||||||

| Low | 8,500 (23.7) | 6,973 (82.0) | 5,135 (60.4) | 1,494 (17.6) | 3,255 (38.3) | 3,456 (40.7) | 5,839 (68.7) | 1,838 (21.6) | 4,152 (48.9) | 3,258 (38.3) | |||||||||

| Middle | 13,426 (37.5) | 10,864 (80.9) | 7,943 (59.2) | 2,346 (17.5) | 5,101 (38.0) | 5,516 (41.1) | 9,195 (68.5) | 2,966 (22.1) | 6,391 (47.6) | 5,324 (39.7) | |||||||||

| High | 13,878 (38.8) | 11,368 (81.9) | 8,403 (60.6) | 2,636 (19.0) | 5,579 (40.2) | 5,530 (39.9) | 9,530 (68.7) | 3,125 (22.5) | 6,408 (46.2) | 5,623 (40.5) | |||||||||

| CCI score | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | .521 | .002 | <.001 | <.001 | .345 | ||||||||||

| 0 | 15,396 (43.0) | 13,256 (86.1) | 9,730 (63.2) | 2,848 (18.5) | 6,127 (39.8) | 6,774 (44.0) | 11,239 (73.0) | 3,587 (23.3) | 7,590 (49.3) | 6,636 (43.1) | |||||||||

| 1 | 4,869 (13.6) | 4,480 (92.0) | 3,530 (72.5) | 1,193 (24.5) | 2,464 (50.6) | 2,405 (49.4) | 3,857 (79.2) | 1,251 (25.7) | 2,839 (58.3) | 2,347 (48.2) | |||||||||

| 2 | 9,739 (27.2) | 8,385 (86.1) | 6,126 (62.9) | 1,782 (18.3) | 3,886 (39.9) | 4,139 (42.5) | 7,080 (72.7) | 2,357 (24.2) | 4,860 (49.9) | 4,022 (41.3) | |||||||||

| ≥3 | 5,800 (16.2) | 5,220 (90.0) | 4,118 (71.0) | 1,363 (23.5) | 2,877 (49.6) | 2,686 (46.3) | 4,443 (76.6) | 1,531 (26.4) | 3,306 (57.0) | 2,541 (43.8) | |||||||||

| MPRm (%) | .776 | .737 | .199 | .376 | .503 | .732 | .075 | .449 | <.001 | ||||||||||

| <80 | 12,734 (35.6) | 10,397 (81.7) | 7,625 (59.9) | 2,348 (18.4) | 4,917 (38.6) | 5,128 (40.3) | 8,722 (68.5) | 2,887 (22.7) | 6,063 (47.6) | 4,800 (37.7) | |||||||||

| ≥80 | 23,070 (64.4) | 18,808 (81.5) | 13,856 (60.1) | 4,128 (17.9) | 9,018 (39.1) | 9,734 (40.6) | 15,842 (68.7) | 5,042 (21.9) | 10,888 (47.2) | 9,405 (40.8) | |||||||||

| DM duration (yr) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||||||||

| <5 | 11,680 (32.6) | 8,011 (68.6) | 4,415 (37.8) | 793 (6.8) | 2,404 (20.6) | 2,338 (20.0) | 5,635 (48.2) | 1,319 (11.3) | 3,049 (26.1) | 2,488 (21.3) | |||||||||

| ≥5, <10 | 14,655 (40.9) | 12,411 (84.7) | 9,237 (63.0) | 2,540 (17.3) | 5,819 (39.7) | 5,945 (40.6) | 10,638 (72.6) | 3,300 (22.5) | 7,228 (49.3) | 6,038 (41.2) | |||||||||

| ≥10 | 9,469 (26.5) | 8,783 (92.8) | 7,829 (82.7) | 3,143 (33.2) | 5,712 (60.3) | 6,219 (65.7) | 8,291 (87.6) | 3,310 (35.0) | 6,674 (70.5) | 5,679 (60.0) | |||||||||

| Smoking status | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||||||||

| Never | 21,705 (60.6) | 18,577 (85.6) | 14,053 (64.8) | 4,550 (21.0) | 9,255 (42.6) | 9,701 (44.7) | 15,913 (73.3) | 5,129 (23.6) | 11,272 (51.9) | 9,502 (43.8) | |||||||||

| Former | 4,422 (12.4) | 3,087 (69.8) | 1,994 (45.1) | 450 (10.2) | 1,246 (28.2) | 1,132 (25.6) | 2,439 (55.2) | 727 (16.4) | 1,441 (32.6) | 1,332 (30.1) | |||||||||

| Current | 9,677 (27.0) | 7,541 (77.9) | 5,434 (56.2) | 1,476 (15.3) | 3,434 (35.5) | 3,669 (37.9) | 6,212 (64.2) | 2,073 (21.4) | 4,238 (43.8) | 3,371 (34.8) | |||||||||

| Duration of smoking (yr)a) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | .001 | .019 | <.001 | .064 | ||||||||||

| 1–9 | 1,156 (8.2) | 873 (75.5) | 573 (49.6) | 109 (9.4) | 350 (30.3) | 384 (33.2) | 730 (63.1) | 235 (20.3) | 469 (40.6) | 428 (37.0) | |||||||||

| 10–19 | 3,299 (23.4) | 2,362 (71.6) | 1,531 (46.4) | 284 (8.6) | 891 (27.0) | 1,036 (31.4) | 1,950 (59.1) | 624 (18.9) | 1,194 (36.2) | 1,109 (33.6) | |||||||||

| 20–29 | 4,568 (32.4) | 3,330 (72.9) | 2,252 (49.3) | 516 (11.3) | 1,380 (30.2) | 1,494 (32.7) | 2,713 (59.4) | 845 (18.5) | 1,722 (37.7) | 1,480 (32.4) | |||||||||

| ≥30 | 5,076 (36.0) | 4,061 (80.0) | 3,076 (60.6) | 1,020 (20.1) | 2,061 (40.6) | 1,893 (37.3) | 3,259 (64.2) | 1,096 (21.6) | 2,289 (45.1) | 1,685 (33.2) | |||||||||

| Daily smoking amount (packs)a) | .001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||||||||

| <1 | 7,190 (51.0) | 5,537 (77.0) | 3,984 (55.4) | 1,122 (15.6) | 2,538 (35.3) | 2,653 (36.9) | 4,544 (63.2) | 1,553 (21.6) | 3,042 (42.3) | 2,509 (34.9) | |||||||||

| ≥1, <2 | 6,274 (44.5) | 4,599 (73.3) | 3,112 (49.6) | 722 (11.5) | 1,939 (30.9) | 1,932 (30.8) | 3,702 (59.0) | 1,129 (18.0) | 2,372 (37.8) | 1,989 (31.7) | |||||||||

| ≥2 | 634 (4.5) | 495 (78.0) | 338 (53.3) | 84 (13.2) | 206 (32.5) | 214 (33.7) | 404 (63.6) | 117 (18.5) | 268 (42.2) | 207 (32.6) | |||||||||

| Binge drinkingb) | .091 | .281 | .361 | .267 | .195 | .300 | .579 | .082 | .755 | ||||||||||

| No | 5,686 (37.3) | 4,316 (75.9) | 3,025 (53.2) | 2,172 (38.2) | 1,848 (32.5) | 2,013 (35.4) | 3,571 (62.8) | 1,171 (20.6) | 2,331 (41.0) | 2,007 (35.3) | |||||||||

| Yes | 9,542 (62.7) | 7,357 (77.1) | 5,162 (54.1) | 1,307 (13.7) | 3,187 (33.4) | 3,483 (36.5) | 6,078 (63.7) | 1,927 (20.2) | 4,046 (42.4) | 3,349 (35.1) | |||||||||

| Heavy drinkingb) | .296 | .133 | .222 | .451 | .604 | .087 | <.001 | .334 | <.001 | ||||||||||

| No | 8,124 (54.2) | 6,207 (76.4) | 4,330 (53.3) | 1,105 (13.6) | 2,673 (32.9) | 2,925 (36.0) | 5,199 (64.0) | 1,755 (21.6) | 3,388 (41.7) | 2,982 (36.7) | |||||||||

| Yes | 6,855 (45.8) | 5,285 (77.1) | 3,736 (54.5) | 980 (14.3) | 2,296 (33.5) | 2,495 (36.4) | 4,298 (62.7) | 1,309 (19.1) | 2,913 (42.5) | 2,290 (33.4) | |||||||||

| Physical activity (times/wk) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||||||||

| None | 13,313 (37.2) | 11,527 (86.6) | 9,071 (68.1) | 3,100 (23.3) | 6,077 (45.7) | 6,400 (48.1) | 9,873 (74.2) | 3,329 (25.0) | 7,274 (54.6) | 5,699 (42.8) | |||||||||

| 1–2 | 8,022 (22.4) | 6,516 (81.2) | 4,665 (58.2) | 1,290 (16.1) | 2,979 (37.1) | 3,170 (39.5) | 5,518 (68.8) | 1,769 (22.1) | 3,753 (46.8) | 3,238 (40.4) | |||||||||

| 3–4 | 6,086 (17.0) | 4,657 (76.5) | 3,202 (52.6) | 827 (13.6) | 2,049 (33.7) | 2,039 (33.5) | 3,860 (63.4) | 1,197 (19.7) | 2,447 (40.2) | 2,277 (37.4) | |||||||||

| ≥5 | 8,383 (23.4) | 6,505 (77.6) | 4,543 (54.2) | 1,259 (15.0) | 2,830 (33.8) | 2,893 (34.5) | 5,313 (63.4) | 1,634 (19.5) | 3,477 (41.5) | 2,991 (35.7) | |||||||||

| All complication | Macrovascular complications | Microvascular complications | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | CeVD | CVD | PVD | All | NEPH | NEURO | RETINO | |||||||||||

| Adj.HR (95% CI) | p | Adj.HR (95% CI) | p | Adj.HR (95% CI) | p | Adj.HR (95% CI) | p | Adj.HR (95% CI) | p | Adj.HR (95% CI) | p | Adj.HR (95% CI) | p | Adj.HR (95% CI) | p | Adj.HR (95% CI) | p | |

| Smoking status | ||||||||||||||||||

| Never | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||||

| Former | 2.09 (1.99–2.19) | <.001 | 1.60 (1.49–1.66) | <.001 | 1.07 (0.96–1.19) | .220 | 1.39 (1.30–1.49) | <.001 | 1.10 (1.03–1.19) | <.001 | 1.81 (1.72–1.91) | <.001 | 1.27 (1.16–1.39) | <.001 | 1.40 (1.31–1.49) | <.001 | 1.49 (1.39–1.60) | <.001 |

| Current | 1.21 (1.17–1.25) | <.001 | 1.10 (1.08–1.17) | <.001 | 1.04 (0.96–1.11) | .324 | 1.11 (1.06–1.16) | <.001 | 1.04 (0.99–1.09) | .084 | 1.16 (1.11–1.20) | <.001 | 1.06 (0.99–1.13) | .081 | 1.10 (1.08–1.18) | <.001 | 1.05 (1.00–1.10) | .056 |

| Duration of smoking (yr) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Never | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||||

| 1–9 | 1.30 (1.17–1.35) | <.001 | 1.02 (0.94–1.11) | .650 | 0.68 (0.56–0.83) | <.001 | 0.96 (0.86–1.07) | .435 | 0.97 (0.88–1.08) | .635 | 1.18 (1.09–1.27) | <.001 | 1.06 (0.92–1.21) | .410 | 1.05 (0.96–1.16) | .280 | 1.16 (1.05–1.28) | <.001 |

| 10–19 | 1.30 (1.20–1.33) | <.001 | 1.05 (0.99–1.11) | .120 | 0.69 (0.61–0.78) | <.001 | 0.96 (0.89–1.04) | .340 | 0.95 (0.88–1.02) | .162 | 1.18 (1.12–1.25) | <.001 | 1.05 (0.95–1.15) | .337 | 1.03 (0.96–1.10) | .467 | 1.09 (1.02–1.17) | <.001 |

| 20–29 | 1.40 (1.33–1.45) | <.001 | 1.22 (1.15–1.28) | <.001 | 0.97 (0.87–1.07) | .509 | 1.16 (1.09–1.24) | <.001 | 1.06 (0.99–1.12) | .095 | 1.29 (1.23–1.36) | <.001 | 1.07 (0.98–1.16) | .125 | 1.15 (1.08–1.22) | <.001 | 1.13 (1.06–1.20) | <.001 |

| ≥30 | 1.40 (1.38–1.49) | <.001 | 1.35 (1.29–1.42) | <.001 | 1.36 (1.26–1.48) | <.001 | 1.34 (1.27–1.42) | <.001 | 1.15 (1.08–1.22) | <.001 | 1.36 (1.30–1.42) | <.001 | 1.18 (1.10–1.28) | <.001 | 1.35 (1.28–1.42) | <.001 | 1.18 (1.11–1.25) | <.001 |

| Daily smoking amount (packs) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Never | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||||

| <1 | 1.20 (1.14–1.23) | <.001 | 1.11 (1.06–1.16) | <.001 | 1.12 (1.08–1.17) | <.001 | 1.09 (1.03–1.14) | <.001 | 1.04 (0.99–1.09) | .133 | 1.12 (1.08–1.17) | <.001 | 1.05 (1.00–1.11) | .075 | 1.08 (1.03–1.14) | <.001 | 1.05 (1.00–1.11) | .075 |

| ≥1, <2 | 1.70 (1.61–1.74) | <.001 | 1.37 (1.31–1.44) | <.001 | 1.53 (1.47–1.60) | <.001 | 1.30 (1.23–1.38) | <.001 | 1.08 (1.02–1.14) | <.001 | 1.53 (1.47–1.60) | <.001 | 1.28 (1.21–1.36) | <.001 | 1.33 (1.26–1.40) | <.001 | 1.28 (1.21–1.36) | <.001 |

| ≥2 | 1.90 (1.72–2.08) | <.001 | 1.46 (1.30–1.64) | <.001 | 1.78 (1.60–1.98) | <.001 | 1.33 (1.15–1.53) | <.001 | 1.11 (0.96–1.28) | .150 | 1.78 (1.60–1.98) | <.001 | 1.35 (1.17–1.56) | <.001 | 1.51 (1.33–1.71) | <.001 | 1.35 (1.17–1.56) | <.001 |

Values are presented as number of frequency (row %), calculated as (patients with the complication/total patients in the category)×100, rounded to one decimal place. Individual complication counts include overlaps, while all complications exclude them. CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; CeVD, cerebrovascular disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; MPRm, medication possession ratio modified; NEPH, nephropathy; NEURO, neuropathy; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; RETINO, retinopathy. a)Total number for this group=39.4% of the total (35,804). b)Non-drinkers were excluded.

Adjusted for gender, age, household income, CCI score, MPRm, heavy drinking, and physical activity. Adj.HR, adjusted hazard ratio; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; CeVD, cerebrovascular disease; CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; MPRm, medication possession ratio modified; NEPH, nephropathy; NEURO, neuropathy; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; Ref, reference; RETINO, retinopathy.

KSNS

KSNS

E-SUBMISSION

E-SUBMISSION

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite