Abstract

-

Purpose

- This review compares the development of South Korea’s Advanced Practice Registered Nurse (APRN) system the well-established APRN system in the United States and provides recommendations for future improvements to the APRN system in South Korea.

-

Methods

- To compare the APRN systems between the two countries, an integrative literature review was conducted using multiple databases and professional nursing organization documents and reports from both the United States and South Korea.

-

Results

- Issues were identified in five major domains: (1) research evidence, (2) education and training, (3) the scope of practice, (4) financial mechanisms, and (5) public awareness and acceptance.

-

Conclusion

- Recommendations are made in four areas: (1) building evidence to support APRN programs; (2) strengthening APRN education; (3) establishing legal support and reimbursement mechanisms; and (4) improving public awareness and acceptance of APRNs.

-

Key words: Advanced practice nursing; Health policy; Health workforce; Nurse practitioners; Scope of practice

Introduction

In the United States, Nurse Practitioner (NP) programs have evolved over nearly 60 years since their inception in 1965 [1]. The United States introduced the NP roles in response to the nationwide primary care provider shortage created by expanding Medicaid/Medicare coverage [1]. Since then, the primary care demand has continued to rise in the United States due to its own aging population and physician shortage. Indeed, national nursing professional organizations noted that “demand for health care continues to rise, fueled by the growth of its aging population and the continued shortage of primary health care providers,” and argued that NPs could help meet this need. As of 2023, Advanced Practice Registered Nurse (APRN) in the United States workforce exceeds 385,000 licensed NPs nationwide that contributes to over 1 billion patient visits each year, which is projected to grow further [2].

Today’s healthcare environment in South Korea is having similar challenges such as its aging populations, rising chronic illnesses, and persistent shortages of healthcare professionals [3,4]. These pressures have led to increasing demands for effective and high-quality care and intensified interest in APRNs [5]. Patients and families are no longer satisfied with one-size-fits-all services—they seek more specialized, individualized nursing care that fits their specific health conditions and healthcare needs [6]. Concurrently, South Korea faces persistent provider shortages. South Korea has one of the lowest doctor-to-population ratios among the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, with approximately 2.6 physicians per 1,000 people [7]. Critical specialties—such as pediatrics, emergency medicine, and geriatrics—are especially understaffed, and many physicians prefer highly paid elective fields (e.g., dermatology, cosmetic surgery) over essential health services [8]. These shortages are felt acutely in rural and under-served areas: rural provinces have less than half the physician density of Seoul, leading to double the risk of delayed critical care [8,9]. The combination of these high demand and limited supply has further stressed a hospital-centric, fee-for-service system. South Korea’s system allows free patient choice of providers, which has led to extremely high consultation rates (highest per capita in the OECD) but very short visits [10]. This model incentivizes volume over coordination, and leaves primary care underdeveloped [11].

In recent years, South Korea’s healthcare system has been exploring the implementation of APRN programs to address these challenges. South Korea’s healthcare reformers have likewise recognized APRNs as part of the solution [12]. Advanced practice nursing in South Korea dates back to the 1970s, with formal Advanced Practice Nurse (APN) certification introduced in the early 2000s [13]. By 2023, 17,103 certified APNs are practicing in South Korea [14]. However, these APNs have reportedly been underutilized because of restrictive laws and unclear scope of practice; APNs are supposed to function under the supervision of physicians without independent prescriptive authority or a billing mechanism for their practice [15,16]. In 2024, a landmark Nursing Act in South Korea was passed, which established a legal basis for advanced nursing practice [17]. However, actual APRN practice in South Korea still remains limited with a lack of supporting structures in many aspects.

The purpose of this paper is to compare South Korea’s APRN development with the well-established APRN system in the United States and to provide recommendations for future development of the APRN system in South Korea. In this paper, APRN means “a registered nurse (RN) who has completed advanced education and training, typically at the master’s or doctoral level, and is qualified to provide a wide range of advanced healthcare services” [18]. The comparison between South Korea and the United States is made in five domains including: (1) research evidence, (2) education and training, (3) the scope of practice, (4) financial mechanisms, and (5) public awareness and acceptance.

Methods

For the comparison between the two countries, an integrative literature review was conducted. Following the methodological guidance of Whittemore and Knafl [19], this integrative review emphasizes conceptual synthesis and thematic integration rather than exhaustive cataloging of studies, as the included evidence spans diverse methodologies and document types [19]. Literature on APRNs was searched in multiple databases, including PubMed, CINAHL, KCI, and RISS, using the keyword “APRN” and its Korean equivalent, “전문간호사.” For PubMed and CINAHL, revised search terms were applied, as these databases yielded a greater number of irrelevant studies. Only the articles published within the last 10 years were included. For RISS, due to limitations in the search functions, only the term “APRN” was used, and manual screening of titles and abstracts was conducted.

Studies were excluded if they (1) did not specifically address APRN or their policy, education, or practice frameworks; (2) focused solely on other nursing roles (e.g., staff nurses, clinical nurse specialists [CNSs], or nurse aides) without reference to APRNs; (3) were duplicates or conference abstracts without full text; (4) were unrelated to the health systems of the United States or South Korea; (5) were published in non-English or non-Korean languages; or (6) were not peer-reviewed articles.

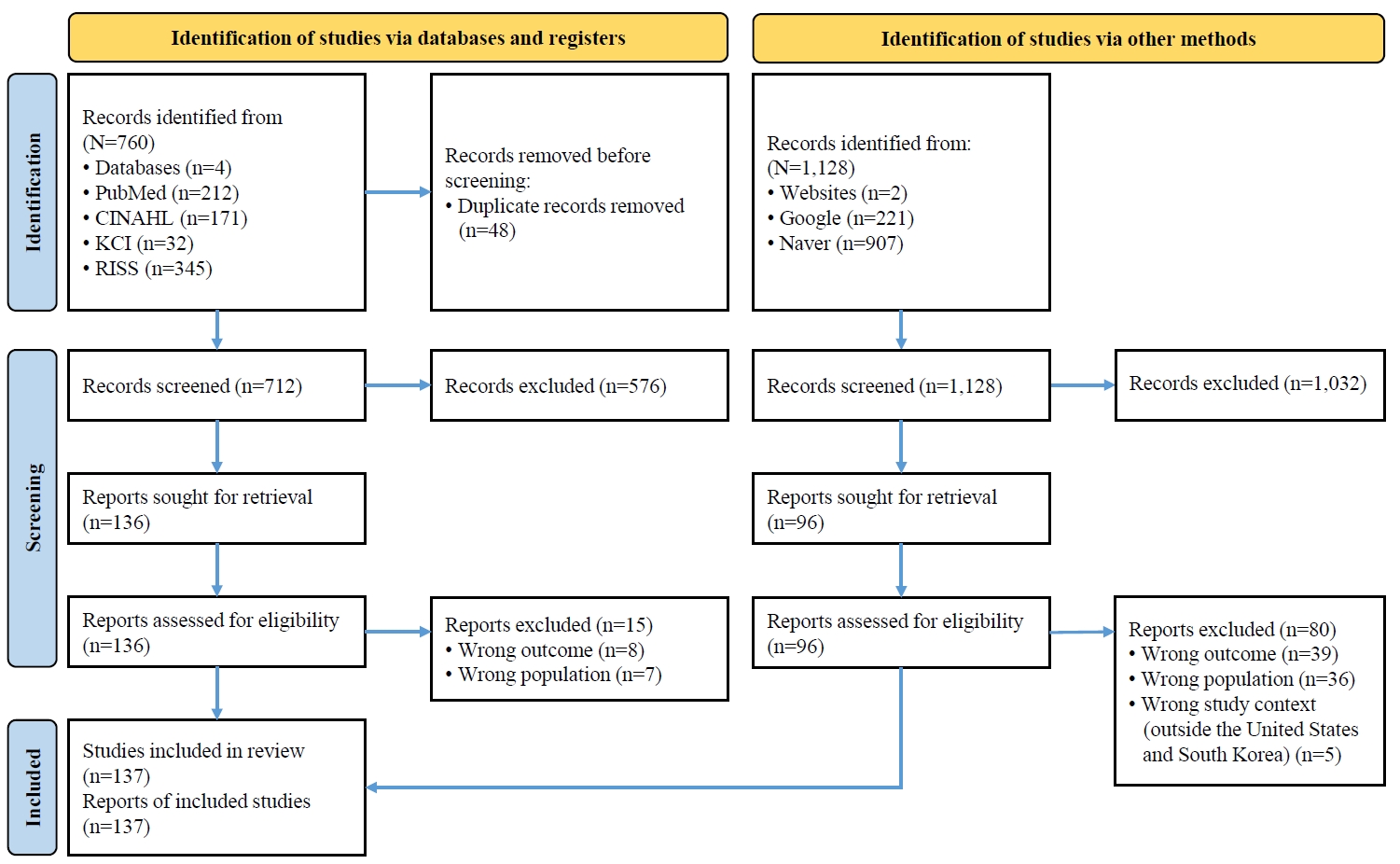

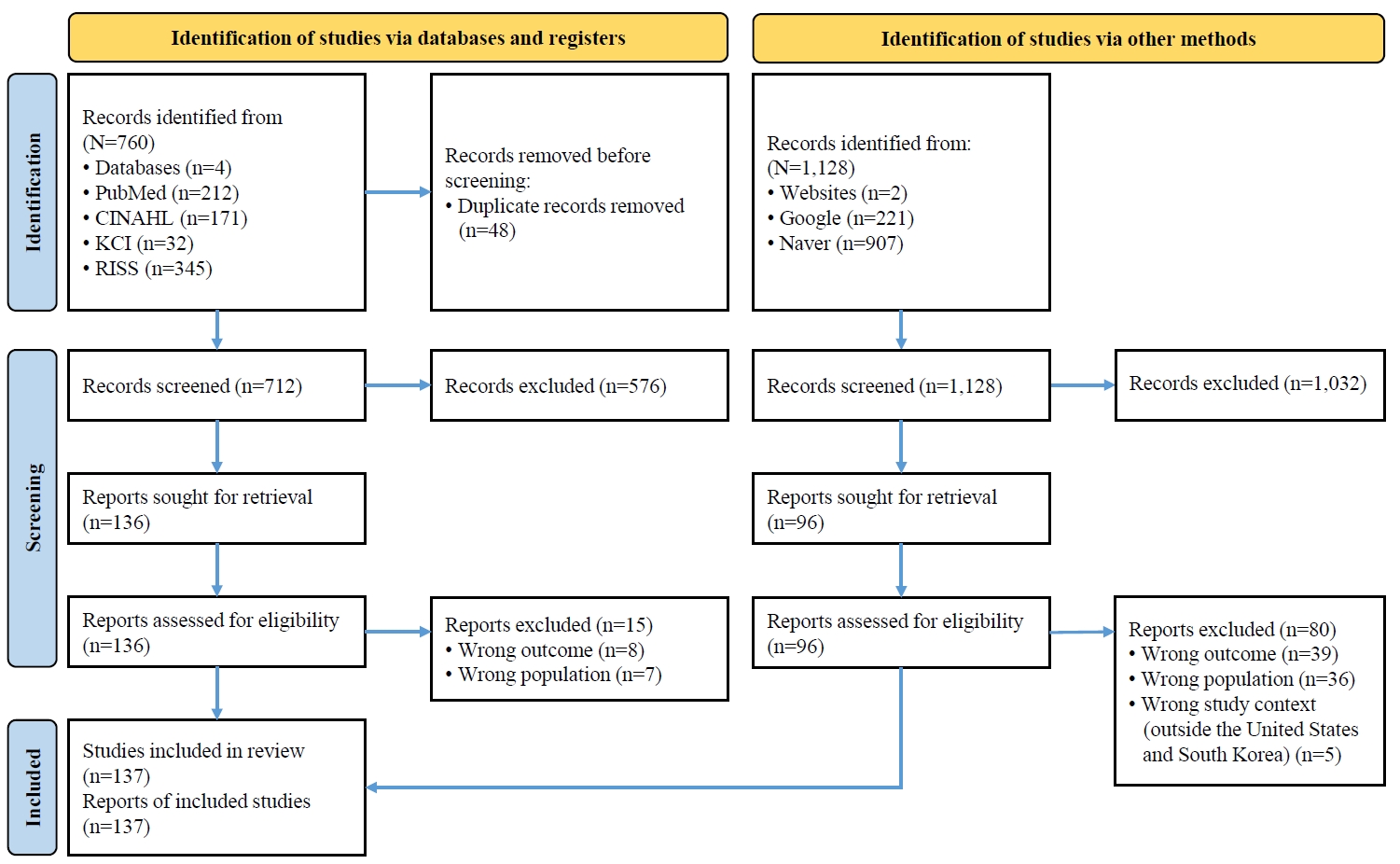

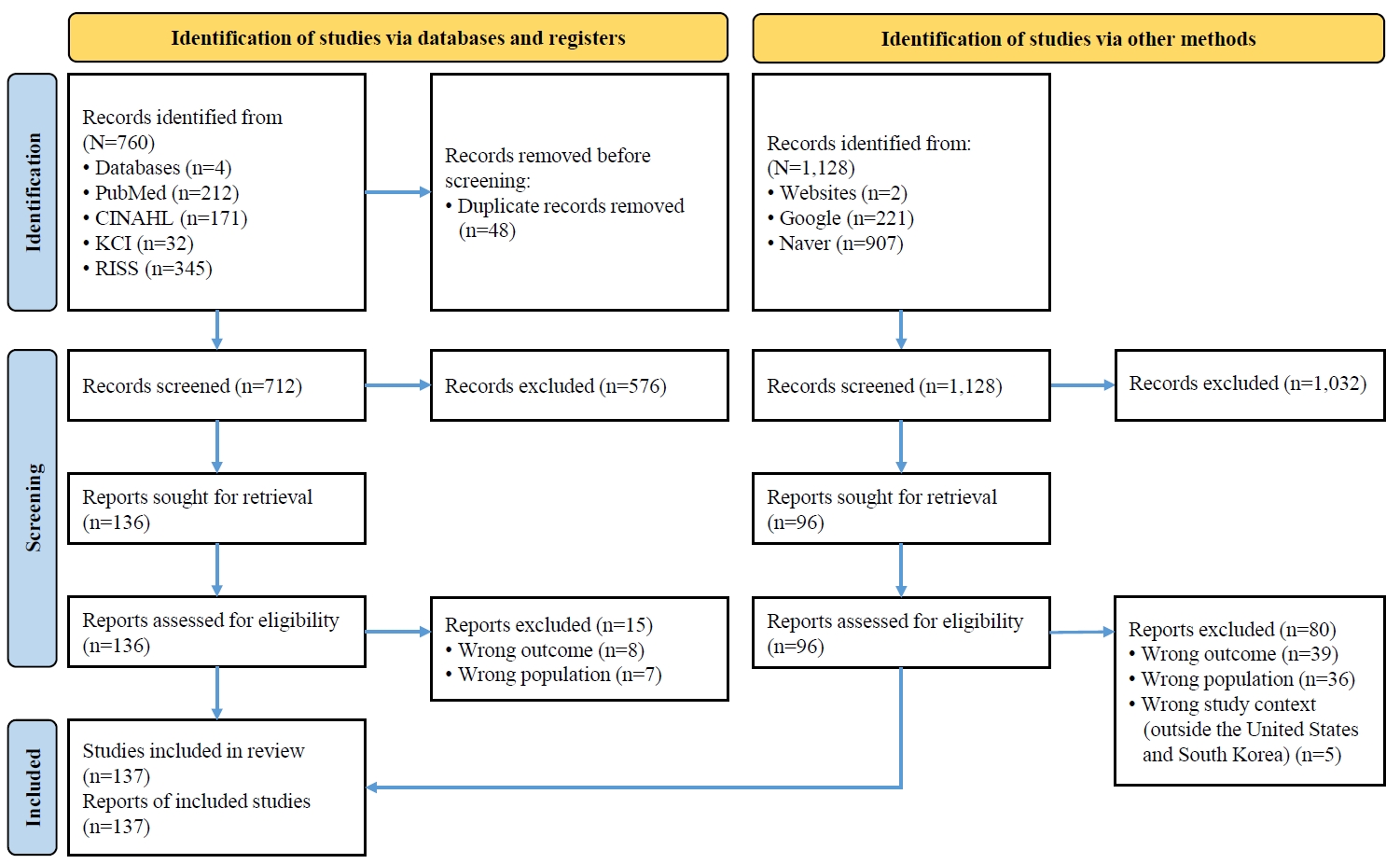

Detailed search terms are presented in Table 1, and Figure 1 provides the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram with detailed information on the selection process for the database search. The database search initially retrieved 760 articles, of which 121 met the inclusion criteria. These comprised research papers, opinion articles, and editorials related to APRNs in the United States or South Korea. In addition, current documents and reports from nursing professional organizations in the United States—including the American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP), American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), American Academy of Nursing (AAN), and American Nurses Association (ANA)—as well as from the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Korean Nurses Association were reviewed. These materials were searched using Google and Naver, limited to publications within the past 10 years, and available as PDF files, yielding 221 results from the United States and 907 results from South Korea. From these, 16 relevant documents and reports were included in the review. The literature search and analysis were conducted between July and August 2025. Documents and reports were excluded if they (1) did not explicitly address APRN-related policy, education, or workforce issues; (2) were press releases, event announcements, or brief news items without substantive policy or practice content; (3) were duplicates or overlapping versions of the same report; (4) lacked accessible full-text or official publication status; or (5) were focused on non-APRN nursing or healthcare workforce topics.

To minimize author bias, multiple strategies were employed throughout the review process. Multiple databases were searched to ensure comprehensive coverage of both United States and South Korean sources, and additional official reports from professional organizations were included to balance peer-reviewed and policy-based perspectives. All potentially relevant articles were screened independently by the author twice to verify consistency in selection and interpretation. Findings were synthesized using a structured comparison framework rather than subjective interpretation, thereby reducing the influence of individual perspectives.

The comparison between the United States and South Korea was chosen for its conceptual and policy relevance. The United States represents one of the most mature and well-defined APRN systems globally, offering a robust model for scope of practice, regulation, and reimbursement. In contrast, South Korea is in the early stages of APRN policy development, having only recently enacted the Nursing Act and continuing to address challenges related to licensure, reimbursement, and role standardization [17]. By contrasting a well-established system (the United States) with an emerging one (South Korea), this study identifies transferable lessons, policy gaps, and context-specific challenges, providing practical insights to guide South Korea’s nursing policy advancement and workforce reform.

Differences between the United States and South Korea

The literature review identified five major areas of comparison between the United States and South Korea, including the research evidence supporting APRN practice and policy; education curriculum and training standards for APRN preparation; scope of practice and related regulatory frameworks; reimbursement mechanisms for APRN-provided services; and public awareness and acceptance of APRNs. These five domains collectively formed the analytical foundation for developing four key areas of policy recommendation: establishing legal and reimbursement support, standardizing education and training systems, clarifying and expanding the scope of practice, and promoting public and interprofessional awareness of APRN roles. The following sections summarize the findings in each comparative area, synthesizing evidence from both United States and South Korean sources.

1. Research evidence

In the United States, a robust body of health services research has documented APRN outcomes, helping to legitimize and guide the related policies. Numerous trials and analyses have compared APRN (often NP-led) care with physician care in primary and acute settings [20]. A landmark randomized trial conducted in the United States found no significant differences in health outcomes, utilization, or patient satisfaction between patients managed by NPs versus physicians, when NPs had comparable authorities and caseloads [21]. Mundinger et al. [21] reported that 6-month health status and 1-year utilization outcomes were statistically equivalent for patients randomized to receive primary care from either a NP or a Doctor of Medicine; neither group showed worse chronic disease control or higher hospital utilization [21]. Other studies conducted in the United States similarly found APRN care to be clinically equivalent (or even superior) to physician care. For instance, a large Veterans Affairs system study showed that patients reassigned to NP primary care had similar clinical outcomes and incurred no higher costs, despite using slightly less specialty and inpatient care. In fact, patients under NP-led care had fewer hospitalizations and maintained equivalent chronic disease control, suggesting that NPs deliver care of comparable quality [22].

A Cochrane systematic review by Laurant et al. [23] further reinforces the evidence base, revealing higher patient satisfaction with NP care and no significant differences in clinical outcomes when compared to physician care. Likewise, an AANP literature review noted that “the majority of cost-focused studies” found NP care cost-effective relative to physicians,’ with similar or better patient outcomes [24]. Studies also documented cost savings from NP management of chronic conditions like diabetes, asthma, and heart diseases [25], as well as reduced hospital readmissions and shorter stays when NPs were involved [26]. For example, hospitals with higher NP staffing spent about 5% less per Medicare patient and saw lower readmission rates [27]. These findings suggest that expanding APRNs can help control costs while maintaining the quality of care.

In contrast, research on APRN outcomes is sparse in South Korea. APRN research must generate evidence to inform policy and reimbursement. Pilot initiatives already undertaken during 2024 provided the data for analysis. For instance, the Ministry of Health and Welfare’s “pilot project on nursing-related tasks”—launched amid the doctor shortage crisis—allowed nurses to legally perform certain procedures under supervision [28]. Evaluating the outcomes of this pilot (e.g., clinical errors, patient throughput, staff feedback) could yield valuable insights on safe task delegation. Additionally, there existed very few studies on if the creation of APRN-led care teams (such as new hospitalist-APN models) could improve access and safety. Such hospitalist–APRN collaborative models may represent a practical mechanism for integrating APRNs into existing hospital systems, fostering interprofessional collaboration and improving continuity of inpatient care [29]. With the limited number of studies, the methods used in the few studies were also limited although a wide range of research methods could be used (e.g., prospective trials, comparative case studies, longitudinal studies, cost-effectiveness studies). One Korean education review also noted that properly trained APNs could “improve patient safety and cost-effectiveness of healthcare” [30], but more peer-reviewed Korean data would be essential.

2. Education and training

In the United States, APRNs (especially NPs) must complete advanced academic programs that build on their RN foundation. Currently, APRN candidates must first obtain a RN license (typically via a Bachelor of Science in Nursing), then pursue a graduate degree. Master’s programs for NPs usually take about 2 years of full-time study, while many institutions now offer Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) programs lasting roughly 4 years [31]. The ANA and accreditation bodies emphasize that many employers and state boards are beginning to require the DNP for new APRNs [32]. Graduates must also pass national certification exams (the American Nurses Credentialing Center [ANCC] or AANP Certification Board) in their specialty, and programs themselves must be accredited by recognized agencies (e.g., the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education or the Accreditation Commission for Education in Nursing) [33].

In addition, APRN programs in the United States mandate hundreds of supervised clinical practice hours. In fact, a joint NP certification statement confirms that a minimum of 500 hours of direct patient care must be completed [34]. Many DNP tracks far exceed this (often targeting 1,000 clinical hours) [35]. These practica occur in varied settings under experienced preceptors, exposing trainees to acute and chronic care management, diagnosis, and prescribing in real-world practice [36]. Also, in the United States, continuing nursing education (CNE) is a mandated component of professional maintenance for APRNs, with many states requiring a specified number of CNE hours for licensure renewal. For example, the ANCC accredits CNE providers and requires NPs to complete continuing education in pharmacology, ethics, and clinical updates as part of national recertification standards [37]. These requirements aim to ensure ongoing clinical competence, align practice with emerging evidence, and promote quality and safety in advanced nursing care.

In contrast, in South Korea, clinical nursing assistants and physician assistants (PAs) typically acquire skills informally rather than through standardized education programs. Most PAs in South Korea enter practice as experienced nurses and learn their advanced tasks by apprenticeship, without a formal PA or APRN curriculum [38]. CNE is not well integrated. Notable, a greater proportion of clinical support nurses reported not receiving pre-service education, with 60.2% (n=100) indicating no prior training, compared to 39.8% (n=66) who did receive such education [39]. This makes outcomes variable and hampers professional development.

3. The scope of practice

The scope of practice refers to the activities that healthcare professionals are legally authorized to perform [40]. In the United States, the current scope of NPs’ practice (legally permitted) is prescribed by state laws, and varies across the United States. The scope of practice can generally be categorized into three: (1) full, (2) reduced, or (3) restricted [40,41]. As of 2025, about 30 states and territories belong to the full category; NPs can independently perform the full range of their training, diagnosing patients, prescribing medications (including controlled substances), managing treatments, and operate their own independent practices without physician supervision. However, NPs are required to have a certain level of experience working under the supervision of a physician or additional training before allowing full practice authority. In the states with the reduced practice scope, NPs have most authority with some limits in certain areas that may need a formal collaborative agreement with a physician (e.g., prescription of certain medications, operation of an independent clinic) [40]. In the states with restricted practice scope (currently 11 states), NPs should practice under the direct supervision of physicians for all of their scope of practice, and they cannot practice independently [40]. However, in some states, these restrictions are loosened as NPs gain experience [40]. Over the past few decades, NPs’ autonomy has been expanded in the United States, driven by: (1) research evidence supporting NPs’ safe and effective care and (2) the increasing nationwide need for more primary care providers [40,41]. By 2024, in the United States, about 30 states and DC had updated their laws to grant full practice authority so that NPs can practice independently without physician oversight [42]. Other states still have some limitations, mainly due to political and professional debates with physician groups [40,43].

In the United States, all 50 states currently license APRNs (NP, CNS, Certified Nurse-Midwife [CNM], and Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist [CRNA]) with well-defined scopes of practice. To achieve clarity, the United States has moved toward a consensus regulatory model. The National Council of State Boards of Nursing’s model recommends four distinct APRN titles with masters-level education and national certification, plus independent prescriptive authority [44]. Studies showed that these legal regimes affected care; full practice authority states had more NPs practicing in rural/underserved areas and improved recruitment, whereas restrictive states correlated with primary-care shortages, higher chronic disease burden, and geographic disparities [45].

Legislation in South Korea has struggled to keep pace with APRN practice. Historically, South Korean law classified nurses as PAs under the Medical Service Act, which granted no autonomous scope [46]. Only in late 2024. South Korea enacted a dedicated Nursing Act. Under the new law, the Minister of Health and Welfare may grant a nurse an APN qualification in addition to the standard nursing license outlined in Article 4 [17,47]. However, many details remain unsettled. The Act itself did not spell out specific role scopes or define all APRN categories, and hospital policies still vary widely. As a result, unlicensed PAs continue to work in “legal limbo” without clear authority [38]. For example, medical technicians who step in for resigning residents have no legal protections if complications occur. Reports noted that many patients in South Korea could not even distinguish whether their caretaker was a doctor, nurse, or PA, because titles and duties were inconsistent and undocumented [48].

Indeed, “PA Nurses” or similar hybrid labels (introduced during recent reform debates) have only created confusion. Currently, PAs’ activities are often unrecorded and unregulated [38]. PAs in Korean hospitals currently operate with no consistent documentation, oversight, or institutional accountability [49]. Moreover, because each hospital sets its own rules regarding the roles of PA nurses, individual nurses often report uncertainty when transitioning to new institutions [50]. International Council of Nurses (ICN) has warned that conflating these roles is “counterproductive” and poses safety risks [51]. The system in South Korea needs to either formally incorporate qualified PAs under the nurse license with proper education or recognize them as separate medical practitioners.

4. Financial mechanisms

In the United States, APRNs are recognized as reimbursable providers under Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance, but payment policies vary. Medicare Part B allows APRNs (NPs, CNMs, CRNAs, CNSs) to bill directly using their own National Provider Identifier (NPI). Under current rules, Medicare pays APRNs 85% of the physician fee schedule for the same service [52]. In Medicaid and commercial plans, all 50 states allow APRNs to enroll and bill, often at parity with physicians or slightly lower rates [25,52]. Some states explicitly require Medicaid to reimburse APRNs at the full physician rate. For example, one study in Medicaid-fee-for-service states with payment parity found NP-led pediatric asthma care costed almost $300 less per patient than physician care [25].

In contrast, in South Korea, the lack of reimbursement mechanisms for APN services in the Korean National Health Insurance system has been pointed out. As noted by Choi et al. [5], there is an “absence of a medical fee schedule” for APN-provided services, which means there is no way for healthcare facilities to bill or be reimbursed for care delivered by an APN [5]. In a healthcare system where virtually all payments are tied to physician services or facility fees, this omission makes hospitals financially reluctant to formally employ APNs as clinical providers [53]. Even if a hospital wanted to utilize APNs (for example, to manage a diabetes clinic), they might not receive insurance reimbursement for those patient visits unless a physician’s name is attached to the service. This financial disincentive significantly hinders APN integration. Korean experts have called for the government to create a reimbursement system and staffing standards for APNs to facilitate their employment and appropriate compensation [54].

5. Public awareness and acceptance

Decades of advocacy have made APRNs a familiar concept in the United States. For instance, a recent survey in the United States found 82% of patients support NPs practicing to the full extent of their training [55]. Similarly, nearly 80% of healthcare professionals (including physicians, nurses, and PAs) in the poll endorsed this view [56]. In practice, many patients report high satisfaction with APRN care; as noted above, several studies even found higher patient satisfaction scores for NP care [57]. Factors contributing to this trust include the longer and more thorough consultations that APRNs tend to provide and the emphasis APRNs place on patient education and preventive counseling [58]. In the United States, the APRN role consistently ranks highly in public esteem: for example, the US News & World Report placed the NP at the top of its 2022 “Best health care jobs” list, reflecting strong public and institutional regard [59]. Americans take pride in having over 385,000 licensed NPs delivering a billion patient visits per year [60]. Such visibility comes from organizing conferences (e.g., annual NP week), public service campaigns, and highlighting APNs’ contributions [61]. For instance, the American College of Nurse-Midwives launched “Our moment of truth: a new understanding of midwifery care,” a public relations initiative to reintroduce midwives as a standard option in women’s health [62]. Nurse anesthetists and specialists use analogous outreach: for example, public-friendly fact sheets and community talks to explain CRNA care and CNS roles [63,64].

In South Korea, patients have traditionally met physicians for diagnosis and treatment, and the concept of a nurse as a primary provider is very new to the public. Subsequently, there may be initial resistance or confusion among patients about the roles of APRNs. Traditional Korean culture accords high respect for physicians, and the ideal physician is an older man with gray hair [65]. Also, traditional Korean culture views nurses as the one who carries out physicians’ orders [65]. With the contemporary nursing education system in South Korea, nurses are gaining stature and respect in Korean culture. Yet, still, the level of public awareness on APRNs would be very low, and intensive efforts will be needed to have people understand NPs as highly qualified professionals, not “second-tier” healthcare providers.

Discussion

Based on the identified differences in APRN systems between the United States and South Korea, the following recommendations are made for the future APRN programs in South Korea. The recommendations are presented in four areas: (1) building evidence to support APRN programs; (2) strengthening APRN education; (3) establishing legal support and reimbursement mechanisms; and (4) improvements public awareness and acceptance of APRNs. The recommendations derived from this review are intended to inform key nursing and health policy stakeholders in both South Korea and the United States, supporting ongoing policy discussions on APRN regulation, reimbursement, workforce integration, and public awareness.

1. Building the evidence to support APRN programs

First of all, data tracking on the APRN workforce needs to be done in South Korea. Implementing routine data tracking to understand the APRN workforce and its deployment would be essential. Currently, official figures suggest around 16,888 Korean APRNs were certified by late 2022 [53], but the actual on-the-job impact is unclear. A recent survey found that of 1,347 certified APRNs, only 29.1% were actually working in advanced practice roles [12]. Many certified APNs continue to work as general RNs, administrators, or even as “clinical nurse practitioner (differently named by hospitals)” with delegated tasks. Complicating the landscape further, there are so-called PAs performing similar functions without formal regulation or role clarity [66]. Therefore, establishing a national APRN registry (possibly under the Nursing Act framework) would allow tracking of how many APRNs are active and what are their specialties and practice settings. Regular workforce studies could then identify geographic or specialty gaps. As Choi [12] observed, the lack of a reporting system “obscures APRNs’ actual activities within healthcare institutions” [12]. Tracking could inform workforce planning and reveal whether policy changes (e.g., new role authorization) actually lead to expanded APRN utilization.

More importantly, evidence generation should extend to public health outcomes. Given the chronic disease epidemic, APRN-led interventions for prevention and chronic disease management—especially in rural areas with severe physician shortages—merit particular attention [67]. In the United States, the states with full practice authority of APRNs witnessed notable improvements in primary care access, especially in rural areas [68]. These policy shifts often led to measurable increases in the supply of primary care providers, enhanced patient access, and reductions in avoidable hospitalizations [69]. South Korea could benefit from similar models. For example, community health programs staffed by APRNs could be piloted to manage hypertension, diabetes, or eldercare, and document outcomes (e.g., improved disease control, reduced hospitalizations). These data would underscore the value of APRNs in primary care—an area the Korean system has struggled with. Building this national evidence base will help persuade stakeholders (physicians, insurers, and the public) to understand the merits of APRNs and guide continuous improvement of APRN education and practice.

2. Strengthening APRN education

To strengthen the APRN workforce in South Korea, the APRN education programs need to be strengthened with collaborative inputs from frontline stakeholders including physicians, experienced PAs, nursing leaders, and nursing educators in revising the APRN curricula. For example, rather than 13 rigidly defined APN specialties, training pathways need to reflect patient and population needs. In the United States, APRN education programs follow a four-role paradigm (NP, CNS, CNM, and CRNA) with specialties embedded in graduate programs. The individual role paradigms of APRNs correspond to a setting or patient group: NPs often focus on primary care (e.g., rural health clinics), clinical nurse specialists work in hospitals (e.g., intensive care unit [ICU] or oncology units), certified nurse-midwives serve maternity care, and nurse anesthetists staff surgical suites [70]. By contrast, South Korea’s current “13-specialty” model (spanning fields from home care to emergency nursing) has outpaced practical deployment [53]. Korea’s 13 APRN fields may not align neatly with service demands; for instance, critical care and emergency fields cover physicians’ shortages there, but those in the fields like infection control or public health may be less visible. Many APNs in South Korea end up working outside their certified field or sharing duties with nurses. Thus, education programs need to be restructured by actual needs.

The curriculum also needs to be strengthened with ample clinical training hours, which will make the trainees enter the workforce with greater confidence and competence, provide better patient care, and smoothen their role integration in clinical teams [71]. Increasing practicum hours and strengthening training standards will produce APRNs who can more independently perform complex tasks (such as comprehensive patient assessments, clinical decision-making, and certain medical procedures) from the start of their careers [72]. Over time, this competence builds trust among physicians and healthcare administrators, who will be more likely to fully utilize APRNs’ skills [73]. Surely, well-prepared APRNs will be better able to demonstrate their values in practice, creating a positive feedback loop: as outcomes improve and become evident, it bolsters the case for continued support and investment in APRN education and roles.

Faculty development is vital in strengthening APRN education in South Korea as well. At present, only 39 institutions in South Korea offer APRN programs, concentrated in metropolitan areas [74]. There is a shortage of qualified faculty with advanced practice experience, and the existing master’s-level programs are already straining academic resources [75]. To expand capacity, South Korea needs to invest in faculty training. Experienced APRNs (both domestic and from abroad) could be recruited as instructors. Existing doctoral or post-master faculty could be sent on fellowships to APRN programs in other countries to learn their curriculum designs. Collaborative faculty appointments with hospitals would allow clinicians to teach APRN students. Additionally, developing an online or blended learning component—as practiced in some countries—could partially alleviate faculty shortages and widen access [76]. The Ministry of Health and Welfare or universities could offer teaching awards or grants to those who develop APRN curricula, creating incentives for faculty engagement.

3. Establishing legal support and reimbursement mechanisms

It would be essential to establish the necessary legal support and reimbursement support for APRNs in South Korea. First, nursing laws need to clearly define the APRN scopes of practice, licensure requirements, and regulatory standards for all APRN roles. As the ICN advises, legislation should “confer and protect” APN titles and outline regulatory mechanisms [77]. Also, South Korea could likewise adopt a unified statutory approach—defining APRN roles, ensuring title protection, and enacting legislation analogous to the Nurse Practice Acts in the United States. Such regulatory clarity would not only safeguard APRN professional status but also promote public trust and interprofessional collaboration by making role boundaries transparent and enforceable.

The South Korean Nursing Act also provides an opportunity to formally absorb current clinical practice nurses into the APRN pathway. South Korea lacks a separate PA system, so it is logical to bring all advanced practice clinicians under one legal framework. Specifically, current clinical nurses performing advanced tasks need to be allowed to obtain APRN certification, perhaps through an accelerated pathway, rather than remain in an ill-defined limbo. This integration would also simplify regulation: rather than multiple nurse/PA titles, South Korea could focus on regulating and compensating a single cadre of APRNs. In practice, achieving these reforms will require addressing vested interests. Debates between the Korean Medical Association and the Korean Nurses Association over the 2021 revision of the ‘Regulations on the Recognition of Advanced Practice Nurse Qualifications’ have intensified, primarily due to unresolved legal ambiguities and the continued absence of clarity on previously identified issues [78]. However, evidence—including ICN position statements—indicates that well-implemented APRN legislation complements physician care, enhancing system capacity without compromising quality [51]. For example, in hospitals in the rural areas of the United States, CRNAs often provide the sole anesthesia coverage under state opt-out laws, freeing physicians to focus on complex cases [79]. Clear, standardized laws in Korea will prevent the current patchwork (where APRN job duties vary by hospital) and protect both providers and patients. As ICN notes, a robust nursing law aligning with international standards will unlock Korea’s “huge untapped potential” by enabling nurses to work to their full scope [51].

Additionally, establishing a reimbursement structure for APRN services is critical to ensure sustainable workforce integration. In the United States, APRNs are recognized as reimbursable providers under Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance, and are able to bill directly using their own NPI at standardized rates [52]. This payment structure has incentivized healthcare systems to fully utilize APRNs in primary and specialty care, contributing to cost-effective and accessible service delivery [80]. By contrast, the Korean National Health Insurance system currently lacks a medical fee schedule for APRN-provided services, creating significant financial disincentives for hospitals to employ APRNs as independent clinicians [54]. Without an official billing and reimbursement mechanism, APRNs remain underutilized, and their contributions to improving access and efficiency go unrecognized. Therefore, a clearly defined reimbursement framework should be introduced alongside legal reforms to promote the formal employment and fair compensation of APRNs.

Such reforms need to be actively championed by Korean nursing associations, whose advocacy will be critical in engaging policymakers, negotiating payment standards, and framing APRN integration as a solution to persistent healthcare access and workforce shortages. The experience in the United States demonstrates that when APRNs are legally recognized and financially supported, they contribute substantially to system efficiency, cost containment, and equitable care delivery. By aligning legislative, regulatory, and reimbursement structures, South Korea can unlock the full potential of its APRN workforce and advance its commitment to high-quality, accessible healthcare.

4. Enhancing public awareness and acceptance

Nursing professional organizations in the United States have invested in public campaigns to raise awareness of APRN roles throughout the past decades. The AANP has launched several national multimedia initiatives. For instance, the “We choose NPs” campaign (beginning 2018) used TV ads, social media, and a patient-focused website to highlight real stories of NP care and advocate for patient access [81]. During the COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) pandemic, AANP’s “NPs combat COVID” ads showcased NPs on the front lines and linked to an informational site for patients [82]. More recently, AANP ran “Lifesaving NP-delivered care” spots telling individual patient narratives of how NPs identified or treated critical conditions [81].

Campaigns need to highlight APRNs’ qualifications and roles (as organizations in the United States run “NP week” events and public service announcements). Sharing research findings (even pilot data) supporting the high quality of APRN care can reassure patients. Media stories featuring patient and community support for APRNs can also build demands. For example, nursing professional associations in the United States often publicize patient testimonials about NP care, and co-brand alongside local health fairs. Continuing such advocacy will help the public understand the new APN roles under the Nursing Act.

Fostering interprofessional dialogue is also important. Hospital systems and clinics can model collaborative practice by integrating APRNs into physician-led teams from the start. Within the healthcare community, changing perceptions is equally important. Previously, some physician groups in South Korea resisted expanding APRNs (viewing them as competitors or assistants). However, targeting opinion leaders—especially doctors in high-need specialties (e.g., emergency and ICU physicians who see staffing crises firsthand)—can help build consensus. Training APRNs in advocacy and health policy is also recommended so that APRNs themselves become ambassadors of their roles [83]. Educational programs could include policy workshops or joint forums with physicians to demonstrate collaborative models. Success stories—such as APRNs improving care in understaffed wards—should be highlighted in medical meetings and joint conferences. Importantly, leaders (e.g., the Korean Medical Association and nursing professional associations) need to be invited to co-develop the necessary guidelines.

Conclusion

South Korea’s recent medical crisis strongly supported the limits of physician-centered care in meeting 21st-century health demands. The nation stands at a pivotal moment for APRN practice. Recent legislative changes opened the door for APRNs to help mitigate healthcare provider shortages, but made it clear that this potential requires intentional actions. Strengthening the APRN workforce offers a proven path to increasing capacity and resilience. In this paper, APRN systems between the United States and South Korea were compared. The recommendations outlined in this paper are grounded in the best practices drawn from the experience in the United States. Yet, the concepts from the APRN system in the United States need to be carefully translated into Korean policy, education, and practice languages because of prominent differences in healthcare systems and cultures between the two countries. By learning from the APRN system in the United States and tailoring it to local needs, South Korea’s nursing and healthcare leaders can ensure that its APRN program initiative is a successful and sustainable endeavor, ultimately making significant positive impacts on the nation’s health.

Article Information

-

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

Acknowledgements

None.

-

Funding

None.

-

Data Sharing Statement

Please contact the corresponding author for data availability.

-

Author Contributions

Conceptualization or/and Methodology: EOI, DMK. Data curation or/and Analysis: EOI, DMK. Funding acquisition: none. Investigation: none. Project administration or/and Supervision: none. Resources or/and Software: none. Validation: none. Visualization: none. Writing: original draft or/and Review & Editing: EOI, DMK. Final approval of the manuscript: all authors.

Figure 1.Flow diagram included searches. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Table 1.Search strategies

|

Database |

Search terms |

|

PubMed |

( "Advanced Practice Registered Nurse"[Title] OR "Advanced Practice Nurse"[Title] OR APRN[Title] OR "Nurse Practitioner"[Title] OR NP[Title] OR "advanced practice nursing"[MeSH Terms] OR "nurse practitioners"[MeSH Terms] ) AND ( "United States"[Title] OR "U.S."[Title] OR USA[Title] OR America[Title] OR "South Korea"[Title] OR Korea[Title] OR "Republic of Korea"[Title] OR "United States"[MeSH Terms] OR "Republic of Korea"[MeSH Terms] ) AND ( "scope of practice"[Title] OR "practice authority"[Title] OR autonomy[Title] OR "prescriptive authority"[Title] OR regulation[Title] OR licensure[Title] OR credentialing[Title] OR billing[Title] OR reimbursement[Title] OR "health policy"[Title] OR legislation[Title] OR "scope of practice"[MeSH Terms] OR "professional autonomy"[MeSH Terms] OR "prescriptions"[MeSH Terms] OR "legislation, nursing"[MeSH Terms] OR "licensure, nursing"[MeSH Terms] OR "health policy"[MeSH Terms] ) |

|

CINAHL |

(TI "Advanced Practice Registered Nurse" OR TI "Advanced Practice Nurse" OR TI APRN OR TI "Nurse Practitioner" OR TI NP OR MH "Advanced Practice Nursing" OR MH "Nurse Practitioners") |

|

AND |

|

(TI "United States" OR TI "U.S." OR TI USA OR TI America OR TI "South Korea" OR TI Korea OR TI "Republic of Korea" OR MH "United States" OR MH "Republic of Korea") |

|

AND |

|

(TI "scope of practice" OR TI "practice authority" OR TI autonomy OR TI "prescriptive authority" OR TI regulation OR TI licensure OR TI credentialing OR TI billing OR TI reimbursement OR TI "health policy" OR TI legislation OR MH "Scope of Practice" OR MH "Professional Autonomy" OR MH "Prescriptions" OR MH "Legislation, Nursing" OR MH "Licensure, Nursing" OR MH "Health Policy") |

|

KCI |

("전문간호사" OR "전문간호사 제도" OR "전문간호사 역할") AND ("업무범위" OR "권한" OR "처방권" OR "규제" OR "면허" OR "자격" OR "수가" OR "보상" OR "법률") |

|

RISS |

전문간호사 |

References

- 1. Buppert C. Nurse practitioner’s business practice and legal guide. 7th ed. Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2021.

- 2. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. Nurse practitioner profession grows to 385,000 strong [Internet]. American Association of Nurse Practitioners; 2023 [cited 2025 Jul 29]. Available from: https://www.aanp.org/news-feed/nurse-practitioner-profession-grows-to-385-000-strong

- 3. Namkung EH, Kang SH. The trend of chronic diseases among older Koreans, 2004-2020: age-period-cohort analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2024;79(9):gbae128. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbae128ArticlePubMed

- 4. Hong YC. Adequacy of the physician workforce for preparing for future society in Korea: an English translation. Ewha Med J. 2024;47(4):e64. https://doi.org/10.12771/emj.2024.e64ArticlePubMedPMC

- 5. Choi SJ, Kim YH, Lim KC, Kang YA. Advanced practice nurse in South Korea and current issues. J Nurse Pract. 2023;19(9):104486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2022.10.015Article

- 6. Choi CJ, Hwang SW, Kim HN. Changes in the degree of patient expectations for patient-centered care in a primary care setting. Korean J Fam Med. 2015;36(2):103-112. https://doi.org/10.4082/kjfm.2015.36.2.103ArticlePubMedPMC

- 7. Kim SJ. A model for projecting the number of doctors in South Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2025;66(3):195-201. https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2024.0400ArticlePubMedPMC

- 8. Smith G, Brake J. South Korea’s healthcare system gets a checkup [Internet]. East Asia Forum; 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 24]. Available from: https://eastasiaforum.org/2024/07/22/south-koreas-healthcare-system-gets-a-checkup/

- 9. Lee KS, Lee H, Park JH. Association between residence location and pre-hospital delay in patients with heart failure. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(12):6679. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126679ArticlePubMedPMC

- 10. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. OECD reviews of public health: Korea: a healthier tomorrow. OECD Publishing; 2020.

- 11. Kim CN, Yoon SJ. Reinforcing primary care in Korea: policy implications, data sources, and research methods. J Korean Med Sci. 2025;40(8):e109. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2025.40.e109ArticlePubMedPMC

- 12. Choi SJ. Legislation of medical support tasks in the Nursing Act as a foundation for nursing professionalism and role expansion. Korean J Adult Nurs. 2025;37(2):69-75. https://doi.org/10.7475/kjan.2025.0403Article

- 13. Seol M, Shin YA, Lim KC, Leem C, Choi JH, Jeong JS. Current status and vitalizing strategies of advanced practice nurses in Korea. Perspect Nurs Sci. 2017;14(1):37-44. https://doi.org/10.16952/pns.2017.14.1.37Article

- 14. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Health and welfare statistical year book 2024. Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2024.

- 15. Kim M, Kim I, Lee Y. A study on legal coherence of legislations related to nursing services: focusing on registered nurse, midwife, advanced practice nurse and nurse assistant. Health Soc Welf Rev. 2018;38(3):420-457. https://doi.org/10.15709/hswr.2018.38.3.420Article

- 16. Kim EM, Choi SJ. Reflections on the prospects of Korean advanced practice nurses : based on Flexner’s professional characteristics. J Korean Crit Care Nurs. 2023;16(3):1-10. http://doi.org/10.34250/jkccn.2023.16.3.1Article

- 17. Nursing Act, Law No. 20445 (Sep 20, 2024) [Internet]. Ministry of Government Legislation; 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 21]. Available from: https://www.law.go.kr/법령/간호법

- 18. Boehning AP, Punsalan LD. Advanced practice registered nurse roles [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023 [cited 2025 Jul 19]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK589698/

- 19. Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(5):546-553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.xArticlePubMed

- 20. Htay M, Whitehead D. The effectiveness of the role of advanced nurse practitioners compared to physician-led or usual care: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud Adv. 2021;3:100034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnsa.2021.100034ArticlePubMedPMC

- 21. Mundinger MO, Kane RL, Lenz ER, Totten AM, Tsai WY, Cleary PD, et al. Primary care outcomes in patients treated by nurse practitioners or physicians: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2000;283(1):59-68. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.283.1.59ArticlePubMed

- 22. Liu CF, Hebert PL, Douglas JH, Neely EL, Sulc CA, Reddy A, et al. Outcomes of primary care delivery by nurse practitioners: utilization, cost, and quality of care. Health Serv Res. 2020;55(2):178-189. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13246ArticlePubMedPMC

- 23. Laurant M, van der Biezen M, Wijers N, Watananirun K, Kontopantelis E, van Vught AJ. Nurses as substitutes for doctors in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7):CD001271. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001271.pub3ArticlePubMedPMC

- 24. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. Literature on NP cost effectiveness discussion paper [Internet]. American Association of Nurse Practitioners; 2025 [cited 2025 Jul 21]. Available from: https://www.aanp.org/advocacy/advocacy-resource/position-statements/nurse-practitioner-cost-effectiveness

- 25. Harrison JM, Kranz AM, Chen AY, Liu HH, Martsolf GR, Cohen CC, et al. The impact of nurse practitioner-led primary care on quality and cost for Medicaid-enrolled patients in states with pay parity. Inquiry. 2023;60:469580231167013. https://doi.org/10.1177/00469580231167013ArticlePubMedPMC

- 26. Morgan PA, Smith VA, Berkowitz TS, Edelman D, Van Houtven CH, Woolson SL, et al. Impact of physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants on utilization and costs for complex patients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(6):1028-1036. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00014ArticlePubMed

- 27. Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Brom HM, Todd BA, Barnes H, Cimiotti JP, et al. Value of nurse practitioner inpatient hospital staffing. Med Care. 2021;59(10):857-863. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000001628ArticlePubMedPMC

- 28. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Pilot project related to nurse scope of work: division of nursing policy [Internet]. Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 28]. Available from: https://www.mohw.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10504000000&bid=0030&act=view&list_no=1480594

- 29. Lee JH. Collaboration model between dedicated physicians and nurses in specialty-centered hospitals attracts attention. Medical Times [Internet]. 2025 Mar 3 [cited 2025 Oct 21]. Available from: https://www.medicaltimes.com/Main/News/NewsView.html?ID=1162616

- 30. Jeong JS. The current situation of nurse practitioner education focusing on clinical practicums in Korea. Jpn J Nurs Health Sci. 2016;14(2):43-47. https://doi.org/10.20705/jjnhs.14.2_43ArticlePubMed

- 31. Waldrop J, Reynolds SS, McMillian-Bohler JM, Graton M, Ledbetter L. Evaluation of DNP program essentials of doctoral nursing education: a scoping review. J Prof Nurs. 2023;46:7-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2022.11.009ArticlePubMed

- 32. American Nurses Association. What is a nurse practitioner? [Internet]. American Nurses Association; 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 28]. Available from: https://www.nursingworld.org/content-hub/resources/becoming-a-nurse/what-is-nurse-practitioner/

- 33. Dugan MA, Altmiller G. AACN Essentials and nurse practitioner education: competency-based case studies grounded in authentic practice. J Prof Nurs. 2023;46:59-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2023.02.003ArticlePubMed

- 34. American Academy of Nurse Practitioners Certification Board. AANPCB response to COVID-19 pandemic: changes in certification testing and deadlines [Internet]. American Academy of Nurse Practitioners Certification Board; 2020 [cited 2025 Jul 28]. Available from: https://www.aanpcert.org/newsitem?id=105

- 35. Stager SL, Mitchell S, Bigley MB, Kelly-Weeder S, Fogg L. Exploring clinical practice hours in postbaccalaureate-to-doctor of nursing practice nurse practitioner programs. Nurse Educ. 2024;49(1):8-12. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNE.0000000000001506ArticlePubMed

- 36. Elvidge N, Hobbs M, Fox A, Currie J, Williams S, Theobald K, et al. Practice pathways, education, and regulation influencing nurse practitioners’ decision to provide primary care: a rapid scoping review. BMC Prim Care. 2024;25(1):182. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02350-3ArticlePubMedPMC

- 37. Todd BA, Brom H, Blunt E, Dillon P, Doherty C, Drayton-Brooks S, et al. Precepting nurse practitioner students in the graduate nurse education demonstration: a cross-sectional analysis of the preceptor experience. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2019;31(11):648-656. https://doi.org/10.1097/JXX.0000000000000301ArticlePubMedPMC

- 38. Yum HK, Lim CH, Park JY. Medicosocial conflict and crisis due to illegal physician assistant system in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36(27):e199. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e199ArticlePubMedPMC

- 39. Hong BR, Kim KM. Effect of job stress, emotional labor, and positive psychological capital on the job satisfaction of physician assistants. Korean J Occup Health Nurs. 2019;28(3):176-185. https://doi.org/10.5807/kjohn.2019.28.3.176Article

- 40. Feeney A. Nurse practitioner practice authority: a state‑by‑state guide [Internet]. NurseJournal; 2025 [cited 2025 Jul 29]. Available from: https://nursejournal.org/nurse-practitioner/np-practice-authority-by-state/

- 41. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. State practice environment [Internet]. American Association of Nurse Practitioners; c2023 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.aanp.org/advocacy/state/state-practice-environment

- 42. Jividen S. Full practice authority for nurse practitioners by state [Internet]. Nurse.org; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://nurse.org/education/np-full-practice-authority

- 43. Henry TA. Series details problems with lax nurse‑practitioner training standards [Internet]. American Medical Association; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/scope-practice/series-details-problems-lax-nurse-practitioner-training

- 44. National Council of State Boards of Nursing. APRN regulation [Internet]. National Council of State Boards of Nursing; c2025 [cited 2025 Jul 29]. Available from: https://www.ncsbn.org/nursing-regulation/practice/aprn.page

- 45. Xue Y, Ye Z, Brewer C, Spetz J. Impact of state nurse practitioner scope-of-practice regulation on health care delivery: systematic review. Nurs Outlook. 2016;64(1):71-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2015.08.005ArticlePubMed

- 46. Medical Service Act, Act No. 14438 (Dec 20, 2016) [Internet]. Korea Legislation Research Institute; 2020 [cited 2025 Jul 21]. Available from: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_service/lawView.do?hseq=40970&lang=ENG

- 47. Cho SY. The impact of nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) on healthcare quality and cost effectiveness in advanced countries. Asia Pac J Converg Res Interchange. 2025;11:613-624. https://doi.org/10.47116/apjcri.2025.08.37Article

- 48. Lee ES, Kim SY. Influence of role conflict and professional self-concept on job satisfaction of physician assistant nurses. Korean J Occup Health Nurs. 2022;31(4):198-206. https://doi.org/10.5807/kjohn.2022.31.4.198Article

- 49. Moon H. A integrated study on the current status and improvement direction of physician assistant. J Converg Cult Technol. 2020;6(3):159-166. https://doi.org/10.17703/JCCT.2020.6.3.159Article

- 50. Ryu MJ, Park M, Shim J, Lee E, Yeom I, Seo YM. Expectation of medical personnel for the roles of the physician assistants in a university hospital. J Korean Acad Nurs Adm. 2022;28(1):31-42. http://doi.org/10.11111/jkana.2022.28.1.31Article

- 51. International Council of Nurses. ICN urges South Korea to make the right choice and back the Nursing Act 2023 [Internet]. International Council of Nurses; 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 29]. Available from: https://www.icn.ch/news/icn-urges-south-korea-make-right-choice-and-back-nursing-act

- 52. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Improving Medicare’s payment policies for advanced practice registered nurses and physician assistants [Internet]. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; 2019 [cited 2025 Jul 29]. Available from: https://www.medpac.gov/improving-medicares-payment-policies-for-advanced-practice-registered-nurses-and-physician-assistants/

- 53. Na NR. A study on the current status and development direction of advanced practice nurses and physician assistant nurses: based on Millerson’s characteristics of professionalism. J Health Care Life Sci. 2025;13(2):391-401. https://doi.org/10.22961/JHCLS.2025.13.2.391Article

- 54. Kim MY, Choi SJ, Jeon MK, Kim JH, Kim H, Leem CS. Study on systematization of advanced practice nursing in Korea. J Korean Clin Nurs Res. 2020;26(2):240-253. https://doi.org/10.22650/JKCNR.2020.26.2.240Article

- 55. McKinsey & Company. Telehealth for health care practitioners and consumers [Internet]. McKinsey & Company; 2022 [cited 2025 Jul 29]. Available from: https://connectwithcare.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Telehealth_MC-Branded_PPT_Final.pdf

- 56. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. Poll shows patients overwhelmingly support nurse practitioner working to the full extent of their education and clinical training [Internet]. American Association of Nurse Practitioners; 2022 [cited 2025 Jul 29]. Available from: https://www.aanp.org/news-feed/poll-shows-patients-overwhelmingly-support-nurse-practitioner-working-to-the-full-extent-of-their-education

- 57. Shanmuga Anandan A, Huynh D, Hendy P. Using patient satisfaction scores to compare the performance of nurse practitioners as compared to doctors in direct endoscopy clinics: a novel pilot trial. Cureus. 2025;17(3):e80502. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.80502ArticlePubMedPMC

- 58. McConkey R, Murphy L, Kelly T, Dalton R, Rooney G, Coy D, et al. Patient-reported enablement after consultation with advanced nurse practitioners: a cross-sectional study. J Nurse Pract. 2023;19(9):104764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2023.104764Article

- 59. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. Nurse practitioners secure No. 1 spot across three U.S. News & World Report Best Jobs rankings [Internet]. American Association of Nurse Practitioners; 2025 [cited 2025 Jul 29]. Available from: https://www.aanp.org/news-feed/nurse-practitioners-secure-no-1-spot-across-three-u-s-news-world-report-best-jobs-rankings

- 60. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. AANP spotlights five critical health care trends to watch [Internet]. American Association of Nurse Practitioners; 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 29]. Available from: https://www.aanp.org/news-feed/aanp-spotlights-five-critical-health-care-trends-to-watch

- 61. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. The power of sharing nurse practitioner stories [Internet]. American Association of Nurse Practitioners; 2023 [cited 2025 Jul 29]. Available from: https://www.aanp.org/news-feed/the-power-of-sharing-nurse-practitioner-stories

- 62. American College of Nurse-Midwives. Our Moment of Truth: A public education campaign [Internet]. American College of Nurse-Midwives; [date unknown] [cited 2025 Jul 29]. Available from: https://legacy.midwife.org/Public-Relations#:~:text=Our%20Moment%20of%20Truth%3A%20A,around%20women%27s%20health%20care%20perceptions

- 63. American Association of Nurse Anesthesiology. CRNA fact sheet [Internet]. American Association of Nurse Anesthesiology; c2025 [cited 2025 Jul 29]. Available from: https://www.aana.com/membership/become-a-crna/crna-fact-sheet

- 64. National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists. What is a CNS? [Internet]. National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists; c2025 [cited 2925 Jul 29]. Available from: https://nacns.org/about-us/what-is-a-cns/

- 65. Purnell LD, Paulanka BJ. Transcultural health care: a culturally competent approach. 4th ed. F.A. Davis; 2013.

- 66. Kim M, Oh Y, Lee JY, Lee E. Job satisfaction and moral distress of nurses working as physician assistants: focusing on moderating role of moral distress in effects of professional identity and work environment on job satisfaction. BMC Nurs. 2023;22(1):267. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-023-01427-1ArticlePubMedPMC

- 67. Floriancic N, Garnett A, Donelle L. Chronic disease management in a nurse practitioner-led clinic: an interpretive description study. SAGE Open Nurs. 2024;10:23779608241299292. https://doi.org/10.1177/23779608241299292ArticlePubMedPMC

- 68. DePriest K, D’Aoust R, Samuel L, Commodore-Mensah Y, Hanson G, Slade EP. Nurse practitioners’ workforce outcomes under implementation of full practice authority. Nurs Outlook. 2020;68(4):459-467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2020.05.008ArticlePubMedPMC

- 69. Mileski M, Pannu U, Payne B, Sterling E, McClay R. The impact of nurse practitioners on hospitalizations and discharges from long-term nursing facilities: a systematic review. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(2):114. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8020114ArticlePubMedPMC

- 70. Hayes W, Baker NR, Benson P, O’Keefe LC. The state of advanced practice registered nursing in Alabama. J Nurs Regulat. 2023;13(4):44-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2155-8256(23)00030-3Article

- 71. Park J, Faraz Covelli A, Pittman P. Effects of completing a postgraduate residency or fellowship program on primary care nurse practitioners’ transition to practice. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2021;34(1):32-41. https://doi.org/10.1097/JXX.0000000000000563ArticlePubMed

- 72. Taylor I, Bing-Jonsson PC, Finnbakk E, Wangensteen S, Sandvik L, Fagerström L. Development of clinical competence: a longitudinal survey of nurse practitioner students. BMC Nurs. 2021;20(1):130. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-021-00627-xArticlePubMedPMC

- 73. Torrens C, Campbell P, Hoskins G, Strachan H, Wells M, Cunningham M, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of the advanced nurse practitioner role in primary care settings: a scoping review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;104:103443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103443ArticlePubMed

- 74. Korean Accreditation Board of Nursing Education. Operation guideline of the advanced practice nurses’ training course. Korean Accreditation Board of Nursing Education; 2025.

- 75. Kim MJ, McKenna H, Davidson P, Leino-Kilpi H, Baumann A, Klopper H, et al. Doctoral education, advanced practice and research: an analysis by nurse leaders from countries within the six WHO regions. Int J Nurs Stud Adv. 2022;4:100094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnsa.2022.100094ArticlePubMedPMC

- 76. Mlambo M, Silén C, McGrath C. Lifelong learning and nurses’ continuing professional development, a metasynthesis of the literature. BMC Nurs. 2021;20(1):62. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-021-00579-2ArticlePubMedPMC

- 77. International Council of Nurses. Advanced practice nursing: an essential component of country level human resources for health. 2nd ed. International Council of Nurses; 2020.

- 78. Jeon SH. Legal issues in the amendment of the ‘Advanced Practice Nurse Regulation’. Healthc Policy Forum [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Jul 29];19(3):34-37. Available from: https://www.dbpia.co.kr/journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE10960250

- 79. Feyereisen S, McConnell W, Puro N. Revisiting the effects of state anesthesia policy interventions: a comprehensive look at certified registered nurse anesthetist service provision in U.S. hospitals from 2010 to 2021. J Rural Health. 2025;41(2):e12879. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12879ArticlePubMed

- 80. Barnes H, Maier CB, Altares Sarik D, Germack HD, Aiken LH, McHugh MD. Effects of regulation and payment policies on nurse practitioners’ clinical practices. Med Care Res Rev. 2017;74(4):431-451. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558716649109ArticlePubMedPMC

- 81. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. Media campaigns [Internet]. American Association of Nurse Practitioners; [date unknown] [cited 2025 Jul 29]. Available from: https://www.aanp.org/about/about-the-american-association-of-nurse-practitioners-aanp/media/media-campaigns

- 82. Stucky CH, Brown WJ, Stucky MG. COVID 19: an unprecedented opportunity for nurse practitioners to reform healthcare and advocate for permanent full practice authority. Nurs Forum. 2021;56(1):222-227. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12515ArticlePubMedPMC

- 83. Wheeler KJ, Miller M, Pulcini J, Gray D, Ladd E, Rayens MK. Advanced practice nursing roles, regulation, education, and practice: a global study. Ann Glob Health. 2022;88(1):42. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.3698ArticlePubMedPMC

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

, Dongmi Kim

, Dongmi Kim

KSNS

KSNS

E-SUBMISSION

E-SUBMISSION

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite